OUR RESEARCH AND OPINIONS ON:

350-Unit Trailer Park Project - Wildlife

This project would put 1,400 residents - and their sewage - where many beloved and protected species live graze, and bray.

Project Navigation

References

WHO else lives here?

This land isn’t empty.

It’s occupied.

It’s alive.

Moreno Valley has seen wave after wave of development since the 1980s. The wildlife has been pushed further into the hills with each new neighborhood and warehouse. Now, we’re at the edge, and the hills are being targeted. The proposed 350-unit trailer park sits directly in one of the last remaining open-space foothill zones on the east. This isn’t just dirt.

It's habitat.

It’s home to protected species, native wildlife, and an ecosystem that still clings to this part of the valley.

This land may not have fences. But it’s not disposable.

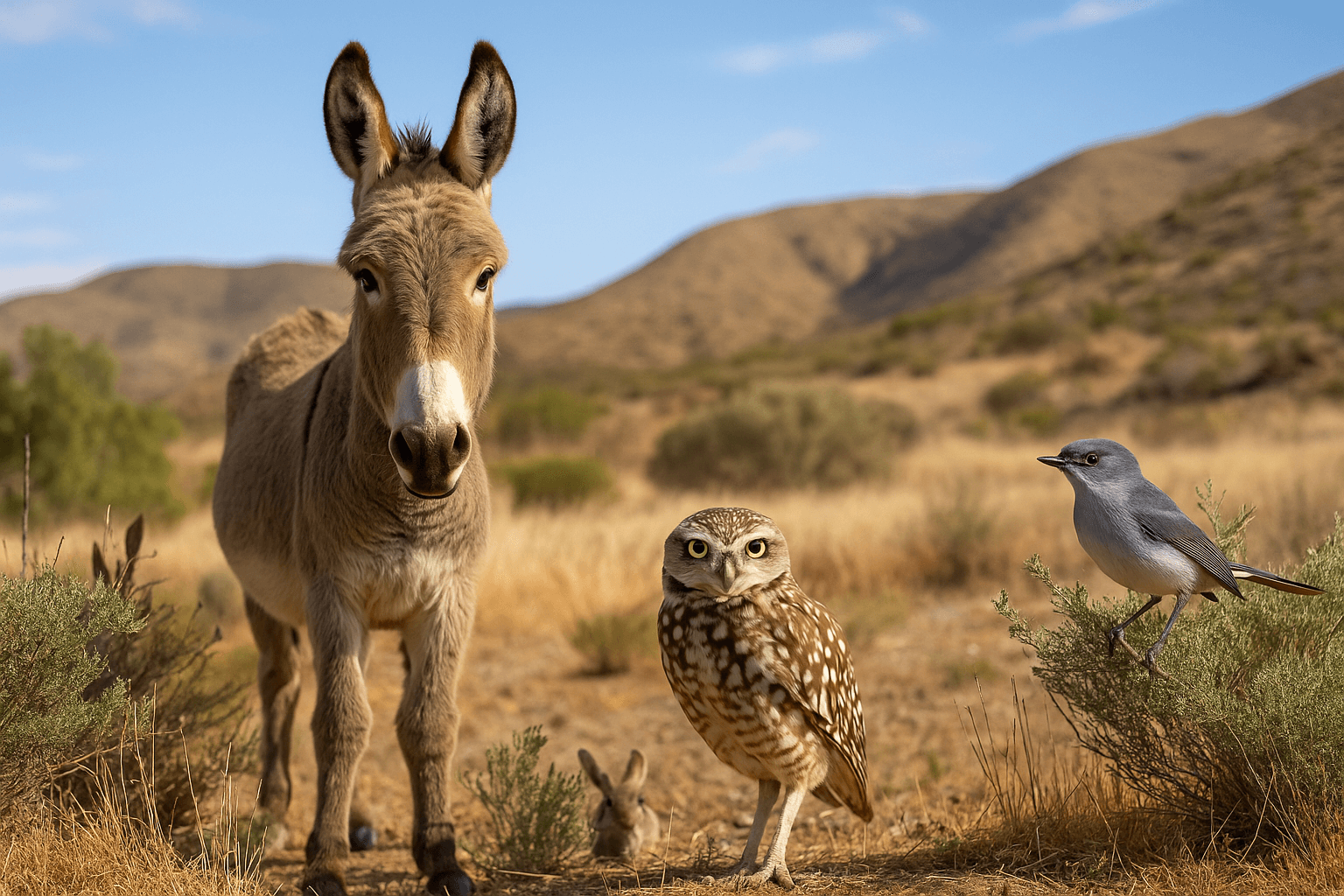

🦉 Burrowing Owls: Present and at Risk

Small, alert, and ground-dwelling, burrowing owls are officially listed by the California Department of Fish & Wildlife as a Species of Special Concern.

They rely on open land and natural burrows, often sharing space with ground squirrels and gophers. These hills have long supported them, and the species has been documented nearby.

The developer’s biological report notes potential presence but offers no clear plan for protection or avoidance.

If grading begins during nesting season, owlets can be buried alive. Once this habitat is gone, the owls won’t move.

They’ll disappear.

🫏 Donkeys: The Living Symbol of the Badlands

To locals, the wild donkeys of East Moreno Valley aren’t a nuisance; they’re part of the land.

Quiet.

Grazing.

Watching.

A reminder that this place wasn’t always paved. This development would cut through their range, fence off grazing space, and flood the area with human activity. The donkeys may not be on a state species list, but belong here. And once they’re gone, they’re not coming back.

And, they do their part by eating weeds that would otherwise burn.

🐦 Coastal California Gnatcatcher: Holding the Edge

Despite its name, the coastal California gnatcatcher isn’t limited to the coast.

Its range extends into these inland foothills.

This small, federally listed Threatened bird depends on fragile sage scrub habitat. Fragmentation, noise, and development pressure have already carved up much of its range. If it’s here and likely is, this project cuts right through its last stronghold.

🐾 Everyone Else We Don’t See (Yet)

The project site and surrounding area likely support:

- Migrating birds and raptors

- Native reptiles (like gopher snakes and whiptails)

- Pollinators, small mammals, and native insects

- Sensitive plant communities tied to seasonal scrub cycles

This land is part of a wildlife corridor recognized by the Western Riverside County Multiple Species Habitat Conservation Plan (MSHCP), a legal framework meant to prevent long-term biodiversity loss in our region.

A dense, isolated development doesn’t just impact one site. It disrupts the flow of life through the entire corridor.

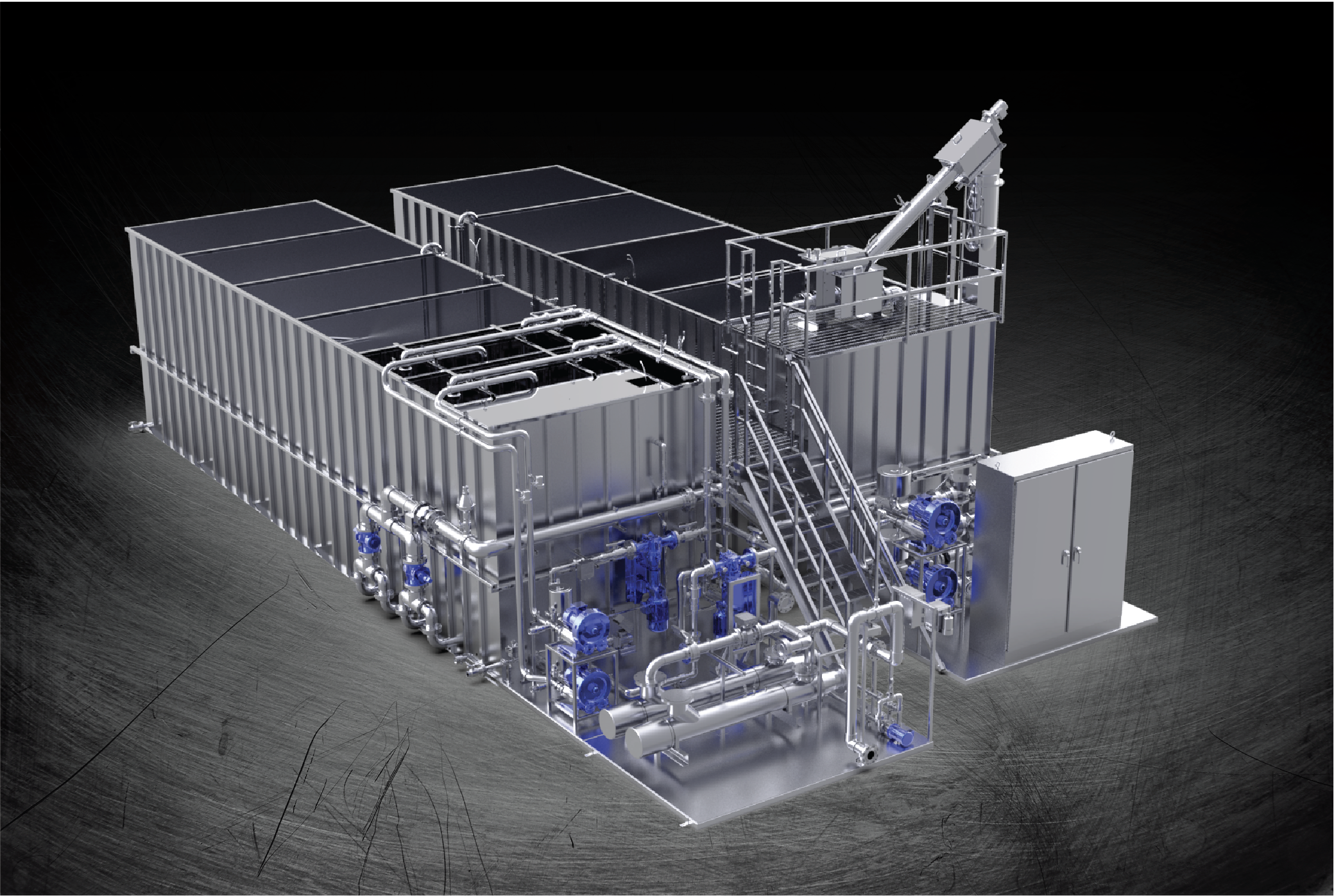

🦠 A Hidden Hazard: The Open-Tank Sewage Plant

The developer proposes a package sewage system, an industrial wastewater treatment plant built on-site, above ground.

Images on the manufacturer’s own website show open tops, exposed piping, and uncovered process areas.

That matters in a sensitive habitat. No commitment has been made to enclose or protect these systems from wildlife exposure. Birds, owls, gnatcatchers, and even insects and mammals could be drawn to open water and chemical byproducts, and there’s no plan in place to keep them safe.

🌱 This Is the Edge of What’s Left

Head west on the 60 freeway and you’ll hit development all the way to the ocean.

Go east, and the land finally opens up.

This stretch of foothills is the last real buffer before the desert. There’s nothing left behind it. No second patch of open space. No hidden refuge.

Do we keep pushing wildlife toward harsher terrain, where humans have air conditioning, and animals don’t?

Once this land is gone, it’s gone.

And the species that depend on it don’t relocate.

They vanish.